- OK BRAIN!

- Posts

- 001: Dopamine, Momentum & Hot Streaks

001: Dopamine, Momentum & Hot Streaks

A newsletter about the science of ideas

Coming up

OK Leader! - The Science of Hot Streaks

OK Systems! - The MAYA Principle

OK Brain! - The Dopamine Edition

…and a bunch of quick links

In order to get the results we desire, we must do two things. We must first create the space to reason in our thoughts, feelings, and actions; and second, we must deliberately use that space to think clearly.

OK Leader! - The Science of Hot Streaks

➔ Leadership in practice

In the early 2000s, football was all about pace and power. But at Barcelona, under Pep Guardiola, a young team led by Xavi, Iniesta, and Messi began exploring new tactics and asked a different question. Not how do we move faster, but how do we move better together?

The answer was Tiki-Taka, a philosophy of rhythm over speed. Each pass a beat, each triangle a note. Short, simple, focused, perfectly timed. It was mocked at first, but La Liga titles, Champions League trophies, and World Cup medals followed.

And it worked because it touched something deeply human — rhythm. A rhythm that stretched from game to game and season to season. During Guardiola’s four years in charge, the team won 14 trophies, including a historic treble - the hottest of hot streaks in Barcelona’s history.

History is full of moments when artists find a rhythm that seems to carry them forward. Stevie Wonder, Bob Dylan, The Beatles, and The Smiths all experienced periods where ideas arrived faster than they could be written down. Artists often talk about these moments in terms of magic and muses. But there’s nothing mystical about it. It’s a finely tuned balance of experimentation and focus.

In a large study analysing the careers of 20,000 artists, film directors, and scientists, Northwestern University economist Dashun Wang and his team found that most artists, directors, and scientists experience a two-stage pattern before their creative “hot streaks”. First, a period of exploration, where they experiment widely with styles or ideas, and then a phase of exploitation, where they focus intensely on what fits their strengths.

The team found that when an episode of exploration was not followed by a rhythm of consistent exploitation, the chance for a hot streak was significantly reduced. Similarly, exploitation alone, not preceded by exploration, also did not guarantee a hot streak. But when exploration was closely followed by exploitation, the researchers noted that the probability of a hot streak consistently and significantly increased.

My bugbear with the “ideas arriving like magic” narrative is that it removes agency. Wang’s work shows that sustained success comes from striking a balance between wild experimentation and extreme focus. It’s daydreaming and doubling down. It’s mind wandering and putting in the hard graft. It’s writing drunk and editing sober. It’s paradoxical. It’s complex. But it’s real! The trick is understanding how to manage this tension. There are methods. Processes. Systems.

OK BRAIN! is a newsletter about starting a conversation with your brain. It’s about the science of where ideas come from and providing leaders with the tools for engineering conditions for breakthrough ideas to flourish. It’s about thinking about thinking. Rules and manifestos. Systems. Checking in with your biases. And brilliant creatives sharing their practices.

This week, I’m sharing a restaurant manifesto and a mental model for thinking about innovation. I’m introducing you to the two faces of dopamine, and giving you a bunch of things to read, watch, and listen to.

I hope you enjoy the rhythm of this week’s newsletter. I love hearing about people’s practices and processes, so please send me your notes.

Hugh

Go deeper:

Notes:

#1 Dolly Parton wrote “Jolene” and “I Will Always Love You” on the same night.

#2 Johnny Marr wrote “How Soon is Now,” “William It Was Really Nothing,” and “Please, Please, Please, Let Me Get What I Want” in the space of four days.

#3 The time between The Beatles’ first and last albums was just seven years and two months.

Whether chemists, physicists, or political scientists, the most successful problem solvers spend mental energy figuring out what type of problem they are facing before matching a strategy to it, rather than jumping in with memorized procedures.

OK Systems! - The MAYA Principle

➔ Systems and frameworks for thinking

In 1979, the world of computing was a stark, bewildering landscape of glowing green text on black screens, demanding users speak to the machine in its own language. For the average person, it felt less like a tool and more like an alien intelligence.

Computers were hidden behind the closed doors of universities and corporations. They were unfamiliar and very intimidating. In the language of design, they were too advanced to be acceptable.

Then a delegation from Apple, including a young Steve Jobs, visited the legendary Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center) and saw something that would change all our lives.

There, on a monitor before them, was not a command prompt, but a desktop. The delegation watched as the cursor, no longer a blinking underscore but an arrow, moved to a small, labeled icon. It was a small, visual metaphor - a picture of a folder.

This wasn't a technological leap. It was a psychological bridge. The team at PARC had taken the terrifyingly abstract concept of a system, with bits and bytes hidden deep within a machine, and cloaked it in the comforting, familiar guise of an office.

Files lived in folders. Programs were started by "clicking" on a button. The entire experience was framed by the very desktop we knew from our work. They kept the advanced technology (the powerful graphics and processing) but made it instantly acceptable through conservative, sensory packaging.

The magic of the graphical user interface (GUI) was that it made an intimidating, complex process understandable through visual metaphor. Apple didn't steal a technology that day. They grasped a principle. A new way of thinking - MAYA, which stands for Most Advanced Yet Acceptable.

Years later, when the iPhone was born, the same principle reigned. It was a revolutionary pocket computer, but the screen was not a blank slate. The Notes app was lined with yellow legal paper. The calculator app looked like a desktop calculator. The Newsstand app was a cozy wooden bookshelf. The technology was stunningly advanced, yet instantly acceptable.

The lesson of MAYA is to build bridges, not take leaps. If you’re selling something surprising, make it feel familiar. If you’re selling something familiar, make it delightfully surprising. It's the sweet spot where innovation meets acceptance, and popularity is born.

Go deeper:

Notes:

#1 In 1970s America, sushi wasn’t popular. To encourage sushi consumption, the California roll was created, combining familiar ingredients (rice, avocado, cucumber, sesame seeds, and crab meat), but in a new way.

#2 The Apple Newton tablet was a financial disaster for Apple in the 1990s, because it introduced a complex technology before the public was ready for it. Apple nailed the MAYA principle with the iPhone.

#3 Google Glass failed the MAYA principle, but Meta’s Ray-Bans didn’t, selling 2 million pairs, with sales tripling in the second quarter of 2025.

It is not merely the feeling that something is familiar. It is one step beyond that. It is something new, challenging, or surprising that opens a door into a feeling of comfort, meaning, or familiarity. It is called an aesthetic aha.

OK Brain! - The Dopamine Edition

➔ Lifting the lid on what’s happening inside our brains when we do creative work

In her brilliant book on writing, Anne Lamott tells the story of her older brother struggling to finish a massive school report on birds. The night before it was due, he sat at the kitchen table, paralysed by the sheer size of the task. Their father, a writer himself, put an arm around him and said, “Bird by bird, buddy. Just take it bird by bird.”

The terror of the “huge report” evaporated. The task instantly shrank to something doable. Just write one sentence about one bird. One paragraph became two. Two became a page. By morning, the report was done.

Dopamine has a bad reputation and rightly so. It’s the molecule that powers our addictions, whether that is to drink, drugs, or doomscrolling. But that same chemical is also the engine of momentum. It’s what turns a single page about a bird into an entire report. If you can fully understand how to control it rather than letting it control you, you’ll master workflows that make the seemingly undoable doable.

To do this, you have to recognise that dopamine works in two ways and balance both.

First, there’s phasic dopamine, the brain’s novelty engine, which releases quick bursts in response to new, unexpected, or rewarding stimuli. It’s the dopamine we’re most familiar with. It drives exploration, motivation, and reward-seeking behavior, encouraging risk-taking and divergent thinking. But it can lead to distraction, impulsivity, or idea fragmentation if you allow it to be overstimulated. Awareness and control are key to progressing from shallow to deep work.

Tonic dopamine is an altogether different motivator. It provides the steady, baseline activation that supports focus, deep thinking, and long-term creative engagement. It allows for presence and cognitive flexibility, enabling us to explore ideas without being hijacked by constant novelty-seeking.

Creative momentum lives in the balance between phasic dopamine’s bursts of inspiration and tonic dopamine’s steady follow-through. Without that balance, ideas either scatter or stall. By engineering our processes to channel dopamine toward meaningful exploration, we can sustain both energy and depth in our work.

To help manage that balance, pay more attention to your social media triggers and cut back. Give your brain room to focus, and create spaces that invite immersion. Lean into deep work, recognise momentum moments when you are in them, and don’t rush to fill boredom.

When Lamott’s father said, “bird by bird,” he wasn’t just offering writing advice, he was describing the neuroscience of momentum. So next time you are stuck, start small. Start anywhere. Bird by bird.

Go deeper:

Notes:

#1 Dopamine is vital for learning as it amplifies memory by tagging experiences as "Important, save for later" in the brain.

#2 Dopamine boosts pattern recognition by tuning signal-to-noise ratios in the brain. It decreases noise and increases signal, making it easier for the brain to detect connections between ideas. That’s why, when solving a crossword puzzle, one correct answer often follows another.

#3 To strengthen tonic dopamine, engage in practices like long-form writing, deep reading, or structured problem-solving. Practicing mindfulness and meditation will also help.

Motivation is what gets you into this game; learning is what helps you continue to play; creativity is how you steer; and flow is how you turbo-boost the results beyond all rational standards and reasonable expectations. That, my friends, is the real art of impossible.

➔ Things to read, watch, listen, and buy

How I Write: Stefan Sagmeister - An always fascinating podcast featuring an always fascinating guest (68 min listen)

Why do some of us love AI, while others hate it? The answer is in how our brains perceive risk and trust - We trust systems we understand. Traditional tools feel familiar, but many AI systems operate as black boxes. (5 min read)

Your brain on uncertainty - Anne-Laure Le Cunff on why, in times of uncertainty, you should act like a scientist. (5 min read)

How to escape the “dopamine crash loop” and rewire your curiosity - More from Anne-Laure Le Cunff on the theme of this week’s dopamine story.

All stories are about survival, connection, and status - “The brain is not interested in fact or truth. The brain is interested in the story” - Will Storr (14 min watch)

The Futures Cone - A useful framework that helps you understand that there is more than a single future to explore, via Ash Mann. (tool)

How to manage great creative teams in these times of burnout - John Peabody on the importance of agency, good feedback, and un-work time (5 min read)

What are you all reading/watching/listening to? Send me your links. I’d love to know what’s stretched your thinking recently.

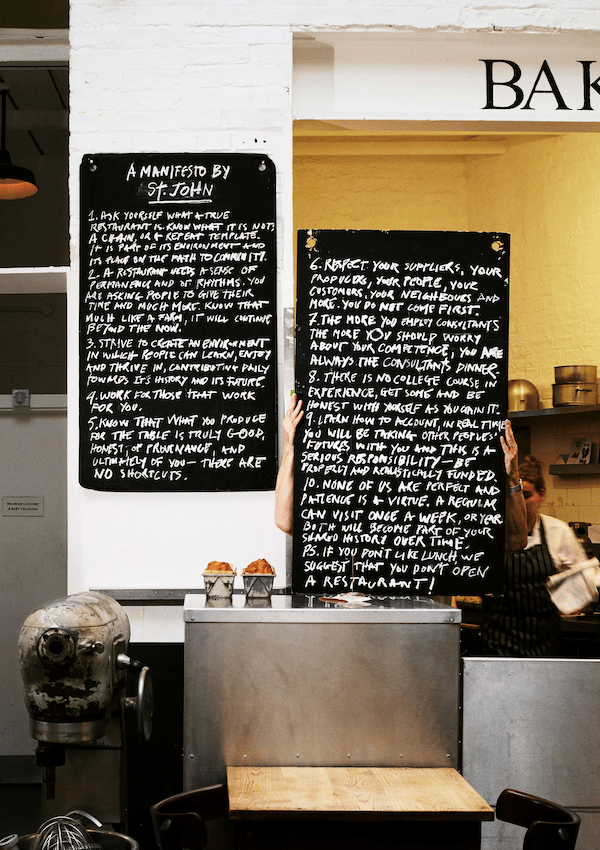

The Rules - St. JOHN Rules for Restaurants

➔ Rules for work, play, and life

St. JOHN is a group of restaurants, bakeries, and a winery, revered by the world’s finest chefs, endlessly imitated, and remarkably unchanged for decades. The wonderful WePresent asked founders Fergus Henderson and Trevor Gulliver to share ten guiding principles for creating and running a restaurant.

“This is not a blueprint to success; there is no formula, but I hope that it is a guide to all that must be considered, noisily and enthusiastically, quietly and reflectively.”

Bookshelf

If you like this sort of stuff ⬆ you’ll love these ⬇

Teresa Amabile’s book argues that the single most powerful motivator for employees is making progress in meaningful work. Even small wins fuel a positive "inner work life," which in turn boosts creativity, productivity, and commitment. |  |

What’s great about Richard Shotton’s third book on behavioural science is that it’s not all theory; it’s filled with techniques brands have used to make their products irresistible to buyers. |  |

There isn’t enough literature on the practice of getting unstuck. I’ve made it my mission to find the most interesting and useful thinking, and bring it to you right here. Adam’s book is a brilliant start! |  |

Thanks for reading. Tell me how this newsletter is helping. I’d love to hear your stories. See you all next week.

Hugh